Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is the leading cause of enteric viral hepatitis worldwide. Recently, autochthonous HEV infection has emerged as a significant concern in Europe, as the EFSA reported, making it a global public health issue. Despite its low prevalence overall, HEV varies significantly in different regions, with higher rates observed in developing countries. In Spain, the general population’s prevalence of anti-HEV antibodies is reported to be 1.1% (Echevarría et al., 2014).

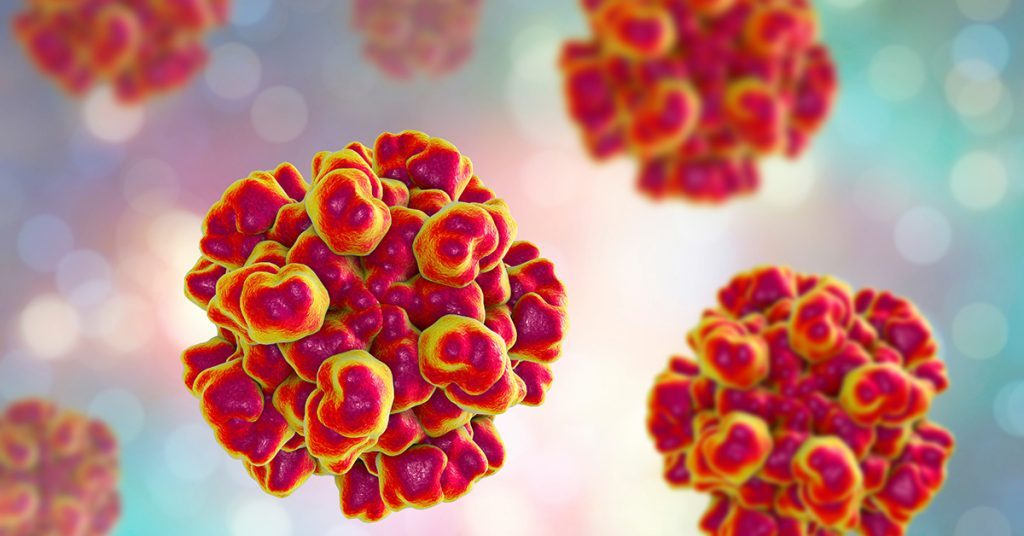

HEV is a small, spherical virus, approximately 27-34 nm in diameter, characterised by a single RNA strand wrapped in an icosahedral-shaped capsid. It belongs to the Hepeviridae family and can infect a wide range of mammalian species, birds (chickens), and fish (trout). Within the Hepeviridae family, two genera are identified: Orthohepevirus, which infects mammals and birds, and Pisci Hepevirus, which targets fish.

HEV in Singapore

The peer-reviewed medical journal Zoonoses and Public Health recently published an article highlighting the escalating incidence of hepatitis E in Singapore. The study revealed a concerning trend, with the number of cases increasing from 1.7 per 100,000 residents in 2012 to 4.1 in 2016 (approximately 1 in 25,000 individuals). Notably, hepatitis E infections were more prevalent among Chinese men aged 55 years and older.

Interestingly, the research findings suggested a shift in the disease pattern. Previously, hepatitis E in Singapore was primarily imported from the Indian subcontinent. However, the study indicated that it is now increasingly prevalent within the resident population.

To arrive at these conclusions, the researchers examined 449 archived serum samples collected between 2014 and 2016 and 36 pig liver samples purchased from markets. Through genetic analysis, they identified most human samples (143 out of 449) as genotype 3, while 21 were genotype 1, and one was genotype 4. The data pointed to genotype 3a as the probable cause of indigenous infections in residents, with genetic similarity to genotype 3a strains detected in pig livers.

These findings provide valuable insights into the changing epidemiology of hepatitis E in Singapore and underscore the importance of continued monitoring and preventive measures to address this emerging public health concern.

Hepatitis E Genotypes and Where They Are Found

The uniqueness of HEV lies in its diverse clinical and epidemiologic profile based on the infection’s origin. This diversity can largely be attributed to the various viral genotypes prevalent worldwide. Human illness caused by HEV is associated with four genotypes, each exhibiting distinct clinical and epidemiologic characteristics in developing and developed countries. In areas where HEV is endemic (genotype 1 in Asia and Africa, genotype 2 in Mexico and West Africa, and genotype 4 in Taiwan and China), cases of hepatitis E typically manifest as large outbreaks and sporadic cases. In developed countries like the United States, isolated cases are more common, linked to genotype 3. Moreover, a novel genotype (genotype 7) has recently been identified in a liver-transplant recipient from UAE who had chronic hepatitis E virus infection, possibly due to frequent camel meat and milk consumption.

|

Characteristics |

Genotype 1 |

Genotype 2 |

Genotype 3 |

Genotype 4 |

|

Geographic Location |

Africa and Asia |

Mexico, West Africa |

Developed Countries |

China, Taiwan, Japan |

|

Transmission route |

Waterborne faecal- oral person-to-person |

Waterborne faecal-oral |

Food-borne |

Food-borne |

|

Groups at high risk for infection |

Young Adults |

Young Adults |

Older Adults (>40 years) and males, immuno-compromised persons |

Young Adults |

|

Zoonotic transmission |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Chronic Infection |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Occurrence of Outbreaks |

Common |

Smaller scale outbreaks |

Uncommon |

Uncommon |

Symptoms and Clinical Outcomes of HEV

HEV infection is typically considered a self-limiting disease in Europe. While the majority of HEV infections are asymptomatic (>70%), symptomatic cases manifest as acute hepatitis, characterised by initial symptoms such as fatigue, asthenia, nausea, and fever. These symptoms may progress to jaundice and elevated liver enzyme levels (Park et al., 2016).

Fortunately, the mortality rate in cases of acute hepatitis is very low, at less than 0.5%. However, pregnant women face a higher risk, with a mortality rate that can reach 25%. Additionally, immunocompromised patients are susceptible to chronic hepatitis development following HEV infection.

HEV infection generally tends to resolve within 1 to 5 weeks, with an estimated incubation period of 2 to 6 weeks. If the virus persists in the individual for over 3 months, it is classified as a chronic infection. Patients with a pre-existing chronic disease or a compromised immune system are at greater risk of developing prolonged (>6 months) chronic hepatitis, potentially leading to fatal liver cirrhosis.

Consequently, individuals who have undergone transplantation had prior liver disease, or experienced haematological malignancies are at the highest risk of developing chronic hepatitis following HEV infection. Healthcare providers must monitor and manage such patients carefully to prevent adverse outcomes.

HEV Routes of Transmission

The transmission of the hepatitis E virus primarily occurs through the faecal-oral route and via contaminated water and food. Ingestion of water or food contaminated with the virus can lead to infection. For instance, drinking water contaminated with the virus or consuming raw or undercooked meat from infected animals, along with fruits, vegetables, or bivalves (such as mussels, cockles, and oysters) washed or irrigated with contaminated water, can all be transmission sources. Additionally, sporadic cases of person-to-person transmission have been observed in relation to blood transfusions or organ transplantation.

Studies focusing on the primary transmission routes have revealed a strong association between the virus and contact with pigs or the consumption of raw or undercooked pork. Higher seroprevalence rates have substantiated this observed in veterinarians, pig farmers, and populations with regular consumption of uncooked pork (Amorim et al., 2017).

Environmental contamination, stemming from human and animal sources, is also recognised as a significant factor in the virus’s spread. Evidence of the virus has been detected in wastewater and sludge from pig slaughterhouses in Europe.

In the case of immunocompromised patients, the main routes of infection include exposure to undercooked infected pork products and through transplants and transfusions.

Detection Methods

HEV detection methods in food are primarily based on various techniques, as reported by the EFSA. These include molecular methods, immunoassays, and infectivity assays using cell cultures or animals. The key distinction lies in that molecular methods can detect the viral genome but do not assess the virus’s infectivity.

Molecular Methods

They involve extracting the virus from a sample, isolating its RNA, and then identifying its genome through PCR techniques. Recently, next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques have been developed for HEV identification using metagenomics.

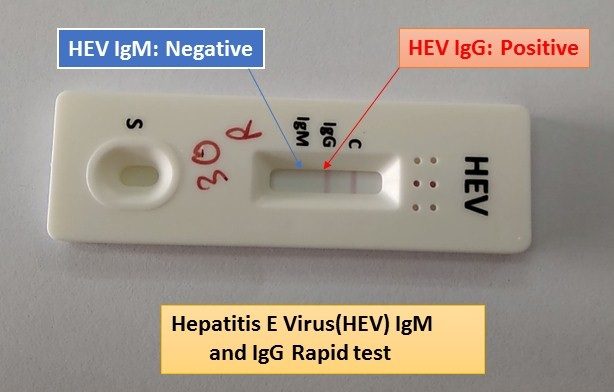

Immunoassays

Immunoassays rely on the host organism’s immune response to identify the causative agent. In the case of HEV, the detection focuses on anti-HEV antibodies, specifically immunoglobulins M and G.

Infectivity Studies

Infectivity studies entail experimental inoculation of animals or cell cultures to study the virus’s ability to cause infection.

Furthermore, serological methods can be employed for food-producing animals to detect specific antibodies against HEV. These methods help identify exposure to the virus and recent infections.

The confirmation of HEV diagnosis involves detecting anti-HEV antibodies in serum and/or the presence of viral RNA in serum or stool samples. However, HEV infection is often underdiagnosed due to the lack of a standardised diagnostic protocol, resulting in an underestimation of its incidence in the population.

Currently, there is no universally standardised method for detecting, quantifying or typing HEV in food.

Hepatitis E Virus Treatment

Hepatitis E commonly resolves on its own without the need for specific antiviral treatment for acute cases. Supportive therapy is recommended by physicians, which includes rest, proper nutrition, adequate fluids, and avoiding alcohol. Patients should consult their physician before taking any medications potentially harming the liver, particularly acetaminophen. In severe cases, hospitalisation may be necessary, and pregnant women should also be considered for hospitalisation.

Some isolated case reports, and case series have suggested that altering immunosuppressive medications and/or utilising antiviral drugs may lead to spontaneous viral clearance in immunocompromised patients with chronic hepatitis E.

In 2011, China registered the first vaccine against the HEV virus, demonstrating its efficacy against the HEV-4 genotype. Nonetheless, its approval in other countries has been withheld due to limited data on its effectiveness against other genotypes.

HEV Prevention Methods

Cooking Thoroughly

While we cannot tell if the meat, especially pig liver, is contaminated with HEV, we can take steps to reduce the risk of foodborne-associated Hepatitis E infection by cooking pork, particularly pig liver, thoroughly until it reaches an internal temperature of 71°C, or when there is no pink meat visible.

Hand Washing

Before serving or consuming food, it is essential to diligently wash your hands with a potent disinfectant cleanser after dealing with raw food. This measure will help eliminate any potential hepatitis E virus that might have contaminated your hands.

Avoiding Unpurified Water

Reducing the risk of infection while travelling to developing countries can be achieved by avoiding the consumption of unpurified water. Boiling or chlorinating the water effectively neutralises HEV, making it safe for consumption.

Additional Measures

- Purchase meat only from businesses approved by the SFA as importers or retailers (in Singapore).

- Refrain from consuming raw or undercooked meat dishes, especially if you have a weakened immune system.

- Ensure raw food is stored in containers with lids to prevent juices from contaminating other raw or ready-to-eat food in the refrigerator.

- Use separate chopsticks and utensils for handling raw and cooked foods to prevent cross-contamination, particularly when using a hot pot.

- Properly clean food appliances and utensils that have come into contact with raw meat.

Conclusion: Hepatitis E Virus (HEV)

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) poses a significant global public health concern, with its prevalence and epidemiology varying across regions. The recent study on HEV infections in Singapore has highlighted the escalating incidence within the resident population, signalling a shift in the disease pattern. The importance of continued monitoring and preventive measures cannot be overstated. Understanding the diverse genotypes and their locations is crucial for effectively addressing this disease. HEV infections are typically self-limiting but can pose serious risks to pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals, necessitating careful management. Transmission primarily occurs through contaminated water and food, especially pork consumption. The lack of standardised diagnostic protocols remains a challenge, warranting the development of effective detection methods. As we strive for better prevention and management strategies, further research and vigilance are essential to combat this emerging public health threat.